Domestic Abuse Through Forced Substance Use

By- Roxanne Guiney

The link between Substance Abuse and Domestic Abuse is very prominent, and these two factors frequently affect the other (Recovery Village, 2019; Rivera et al., 2015). Although many abuse victims willingly use substances to cope, or they entered the relationship after their prior use made them vulnerable, sometimes the aggressive partner more directly influences the victim’s substance use (Phillips, Warshaw, & Kaewken, 2020; Rivera et al., 2015; Warshaw et al., 2014).

According to a report from the National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma & Mental Health, 43% of female domestic violence victims and survivors claimed that their abusers coerced them in some way through substance use (Warshaw et al., 2014). Additional victims and survivors have been physically forced to use substances or drugged unknowingly (Phillips et al., 2020). Once addicted, a reported 60% of their abusers have actively discouraged or sabotaged their victim’s attempts to gain sobriety and have used their victim’s substance use to isolate them from social support (Rivera et al., 2015; Warshaw et al., 2014).

Whether the abuser is forcing their victim to use intoxicating substances, aggressively encouraging or enabling them, or resisting their victim’s efforts to quit, this behavior is often a malicious attempt to keep the victim in the abusive relationship (Rivera et al., 2015; Phillips, Warshaw, & Kaewken, 2020).

Control Through Impairment

Impaired domestic partners are easier to control. Similarly to how human traffickers force their victims to use drugs to make them more compliant, abusers can force their partners to use substances for the same purpose (Recovery First, 2019). When inebriated, people may care less about their situation and not be able to think strategically enough to mobilize resources or assert themselves; furthermore, they are susceptible to memory issues (Phillips et al., 2020; Warshaw et al., 2014). They are also at greater risk of developing mental illnesses such as depression and suicidality, which causes further impairment and lessens credibility when seeking support (Phillips, Warshaw, & Kaewken, 2020; Warshaw et al., 2014). The victim may also blame themselves for their situation because of their substance use and not feel entitled to help (Phillips, Warshaw, & Kaewken, 2020).

Blackmail

An abusive partner may use blackmail in many ways, including through their victim’s use of substances. One way is to coerce their partner to start using drugs by threatening to expose other secrets (Rivera et al., 2015). Once their victim is using, the abuser may also blackmail their partner into compromising situations by threatening to take away their access to the substances or expose their use (Phillips, Warshaw, & Kaewken, 2020; Rivera et al., 2015; Warshaw et al., 2014). For example, in an abusive relationship, they may threaten to report their partner who is engaged in a custody battle at the consequence of the victim losing their children or expose their partner’s use to immigration authorities at the risk of the victim being deported (Phillips, Warshaw, & Kaewken, 2020; Phillips et al., 2020; Warshaw et al., 2014).

Limited Access to Law Enforcement

Another frightening way abusers can use their victim’s substance use against them, especially with illicit drugs, is to limit the victim’s access to law enforcement to stop the abuse (Rivera et al., 2015). Being inebriated can undermine the victim’s testimony, making them lack credibility in court, and even risk them being the one facing charges if the police are alerted (Houry, Reddy, & Parramore, 2006; Rivera et al., 2015). As a result, the victim has little legal protection against their abuser.

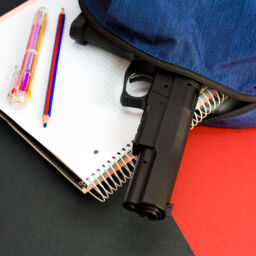

Family Abuse Beyond Intimate Partners

Family abuse through substances is not limited to romantic partners. Elders may become unwillingly addicted to substances after prolonged medication use, including caregivers overmedicating them to make them sleepy or more compliant (Recovery First, 2019; Seniors First BC., n.d.). Parents may also force their children to take strong medications or illicit drugs, often to make the children easier to manage (BBC, 2016; Morris, 2010). In 2016, for example, a Washington couple was discovered injecting their children with heroin to put them to sleep, and several methadone users in the UK were found giving the medication to their children to “soothe” them when sick (BBC, 2016; Morris, 2010).

Looking Ahead

This aspect of domestic abuse is not only infrequent, but often overlooked by mental health professionals, legal professionals, and other advocates of victims and survivors (Phillips et al., 2020; Warshaw et al., 2014). The topic also lacks research, which is both a cause and result of this lack of awareness (Phillips et al., 2020; Rivera et al., 2015; Warshaw et al., 2014). With greater understanding, we will be able to offer the support that victims and survivors need to exit their abusive situations and help them find any necessary treatment and support for their substance use.

We at ARO are here to support you in your personal healing journey to complete well-being. We bring awareness and education to 13 different types of abuse including Narcissistic, Sexual, Physical, Psychological, Financial, Child, Self, Cyberbullying, Bullying, Spousal, Elderly, Isolation and Workplace, and help others heal and find peace. Please support our efforts by going to GoARO.org to learn how you can make an impact on the Abuse Care Community.

References

BBC. (2016, November 2). Washington mother accused of giving children heroin. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-37845998

Houry, D., Reddy, S., & Parramore, C. (2006). Characteristics of Victims Coarrested for Intimate Partner Violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21(11), 1483–92.

Phillips, H., Warshaw, C., & Kaewken, O. (2020). Literature review: Intimate partner violence, substance use coercion, and the need for integrated service models. National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma, and Mental Health. http://www.nationalcenterdvtraumamh.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Substance-Use-Coercion-Literature-Review.pdf

Phillips, H., Warshaw, C., Lyon, E., & Fedock, G. (2020). Understanding substance use coercion in the context of intimate partner violence: Implications for policy and practice. National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma, and Mental Health. http://www.nationalcenterdvtraumamh.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Substance-Use-Coercion-Key-Informant-Themes.pdf

Recovery First Editorial Staff. (2019, August 6). Understanding unwilling drug addiction part 1. Recovery First Treatment Center. https://recoveryfirst.org/blog/understanding-unwilling-drug-addiction-part-1/

Recovery Village. (2019, January 16). Domestic violence resources: How domestic violence and substance abuse are connected. https://www.therecoveryvillage.com/resources/domestic-violence/#4

Rivera, E. A., Phillips, H., Warshaw, C., Lyon, E., Bland, P. J., & Kaewken, O. (2015). The relationship between intimate partner violence and substance use. National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma & Mental Health. http://www.nationalcenterdvtraumamh.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/IPV-SAB-Final202.29.1620NO20LOGO-1.pdf

Seniors First BC. (n.d.) Medication Abuse.

Steven Morris. (2010, July 15) Couple jailed for giving baby methadone. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2010/jul/15/baby-methadone-parents-jailed

Warshaw, C., Lyon, E., Bland, P., Phillips, H., & Hooper, M. (2014). Mental health and substance use coercion surveys. Report from the National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma & Mental Health and the National Domestic Violence Hotline. http://www.nationalcenterdvtraumamh.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/NCDVTMH_NDVH_MHSUCoercionSurveyReport_2014-2.pdf